Room 01

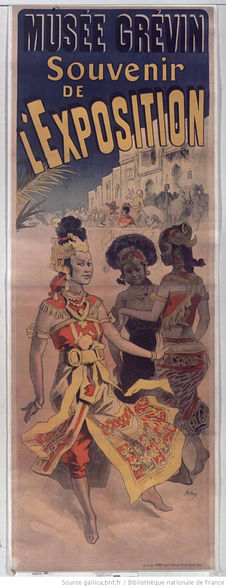

Dance at the World's Fairs

"The troupe of the Cochin-Chinese theater." Paris Colonial Exposition, 1931.

A selection of exposition posters featuring dancers and performers from past world's fairs (1889 - 1931).

Dance: A World Language

What language could be used to link the many peoples and

cultures at these fairs? Words would not do in this exhibition Babylon. What was needed were things that could be understood and appreciated by looking and listening such as the work of a craftsman, a musical performance, a finished print or the moving figures of dance. Culture speaks through dance forms. Asian dances with their celebratory spirit and cultural sophistication caught on not just with regular visitors as well as artists. Although they might not know the particular “grammar” and “vocabulary” of a certain dance traditions, the primary channel through which dance communicates is aesthetic beauty. The Javanese dances that were a sensation at many of the fairs were described by critics at the Paris 1900 fair as “the purest of Asia; … calm and chaste and tranquil, with no beginning and no end as the eternal music of the universe.”[1]

|  |

|---|

Javanese and Khmer

Dance Troupes

Colonial Exhibition, Flag of Holland: Bali dancers,

[press photograph] / Agence Meurisse.

Source: Gallica BnF

Danseuses Cambodgiennes à Marseille,

Exposition Coloniale 1922.

Source: Flickr

The Debut of Khmer and Javanese Dancers

Since 1920s, dancers from all over the world were engaged to perform in commercial theaters in major European cities. Among the most popular was Indian dance.[2] The breakthrough for “Oriental” dance, however, came with the Khmer and Javanese dance troupes in 1889.

"The Java Dancers at the Paris Exhibition." Illustrated London News.

Saturday 06 July, 1889.

Source: The Britsh Newspaper Archive

Universal Exhibition of 1889, Paris. "The Javanese Dancers in the kampong

(rebuilt Javanese village) on the Esplanade of the Invalides," advance sketch for the illustration in a journal. Paris, Carnavalet Museum, D 5256.

Source: Demeulenaere-DouyeÌre, Christiane. Exotiques Expositions: Les Expositions Universelles Et Les Cultures Extra-EuropeÌEnnes, France, 1855-1937; Somogy EÌd. D'Art, 2010.

One admirer included the artist John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), who had visited the exposition and was fascinated by the Tandak dancers. He went on to create a series of oil paintings and sketches of these individual dancers in their costumes.

The Four Tandak dancers performing in the "Kampong Javanais" at Universal Exhibition of 1889, Paris.

The Four Tandak Dancers

at the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris

Tandak is a type of Javanese social dance

performed by men and women accompanied by singing. At the 1889 Paris Exposition, four dancers from the ruler’s court at Solo, Java, were invited to perform this traditional dance at the “Kampong Javanais,” a recreation of a Javanese village at this fair, which formed the backdrop for the dancers.

The Javanese

Gamelan Orchestra

In a 1913 Revue Systèmes d'Information et

Management article, Debussy writes:

"There used to be—indeed, despite the troubles that civilization has brought, there still are—some wonderful peoples who learn music as easily as one learns to breathe. Their school consists of the eternal rhythm of the sea, the wind in the leaves, and a thousand other tiny noises, which they listen to with great care, without ever having consulted any of those dubious treatises. Their traditions are preserved only in ancient songs, sometimes involving dance, to which each individual adds his own contribution century by century. Thus Javanese music obeys laws of counterpoint which make Palestrina seem like child’s play. And if one listens to it without being prejudiced by one’s European ears, one will find a percussive charm that forces one to admit that our own music is not much more than a barbarous kind of noise more fit for a traveling circus."[4]

— Claude Debussy

Claude Debussy's Pagodes (Estampes, 1904), that may have been influenced by the Javanese Gamelan Orchestra.

The Javanese Gamelan Orchestra, 1870-1891.

Source: Collective Stichting National Museum van Wereldculturen

A playlist of traditional Java Gamelan music, performed by the Royal Court Gamelan.

2.

1. "Interior of the Javanese Theater." 1893 Chicago World's Fair.

Source: Worlds Fair Chicago 1893

2. "Javanese Gamelan Orchestra and Topeng masked dancers." 1893 Chicago World's Fair.

1.

Javanese Theater

In 1893 Chicago world’s fair, the exposition

writer Julian Hawthorne was keenly impressed with the Javanese dancers when he saw their performance in the Javanese Theater at Midway Plaisance:

"Their dramatic performance is the most curious thing imaginable. Nothing in it recalls anything else ever seen. […] At a distance, it sounds like the strains of a music box. […] There is no curtain. After the orchestra has taken its place and played for a few minutes, there enter from the little curtained entrances at the sides of the stage five tiny women clad in gorgeous attire and white stockings without shoes. They form in line, and begin a ‘dance’ consisting of slow changes from one to another of the most fantastic, but always graceful poses. […] You hold your breath to see them, and yet nothing else happens. They move on the stage, not by steps, but by edgings-along of their little feet. […] [the male actors] wear a mask most elaborately made and colored, and with a weird and grotesque set of features cast in a certain expression which is curiously in accord with the character represented. […] There are four or five ‘acts’ as they must be called in this extraordinary production. […] I do not know why the play ends when it does any more than I know how it began; I am delighted with all I see, but have not the faintest comprehension of its significance. […] So we march out, and the world seems bigger and stranger than ever."[6]

Auguste Rodin (1840 - 1917) drawing a Cambodian Dancer. The illustration, July 18, 1906, Cl. Émile San Remo. Paris, Rodin Museum, Inv. 197.

Source: Demeulenaere-DouyeÌre, Christiane. Exotiques Expositions: Les Expositions Universelles Et Les Cultures Extra-EuropeÌEnnes, France, 1855-1937; Somogy EÌd. D'Art, 2010.

Rodin and

Cambodian Dancers

"They have brought antiquity back to life for me…They have given me new reasons to think that nature is an inexhaustible source for those who bend down to drink from it… I am man who has dedicated all his life to the study of nature, and who has always admired the works of antiquity: this might help you to imagine the impression made on me by as perfect a performance, which has given antiquity back to me by opening up its mystery to me… For me, I feel how my vision has expanded by looking at them; I have seen higher and further; finally, I understood."[7]

— Auguste Rodin

Cambodian Royal Ballet

and King Sisowath

The royal ballet of Cambodia was established in the

royal courts of Cambodia for court and religious ceremonies as well as entertainment. It dominates the classical dance style in Cambodia. According to the earliest records from the 7th century, this style of dance was originally performed as a funeral rite for kings. During the Angkor period (9th to 15th century), dance was ritually performed at temples. The temple dancers came to be considered as apsaras, semi-divine beings who served as entertainers and messengers to divinities. It dominates the classical dance style in Cambodia.

Video footage of the Royal Ballet of King Sisowath, in early 1900s.

Cambodian Dancers performing at the Exposition Nationale Coloniale Marseille, 1922.

Dance and Architecture

National Colonial Exhibition of Marseille, 1922. Pavilion of Cambodia.

Royal dancers at the entrance of the reconstruction of the temple of Angkor, August 1922.

Photographie F. Detaille. Aix-en-Provence, Archives. Nationales D'outre-mer, fr anom 2Fi 2061

Source: Demeulenaere-DouyeÌre, Christiane. Exotiques Expositions: Les Expositions Universelles Et Les Cultures Extra-EuropeÌEnnes, France, 1855-1937; Somogy EÌd. D'Art, 2010.

National Colonial Exhibition of Marseille, 1922. Pavilion of Cambodia. Royal dancers at the entrance of the reconstruction of the temple of Angkor, August 1922.

Photographie F. Detaille. Aix-en-Provence, Archives. Nationales D'outre-mer, fr anom 2Fi 2061

Source: Demeulenaere-DouyeÌre, Christiane. Exotiques Expositions: Les Expositions Universelles Et Les Cultures Extra-EuropeÌEnnes, France, 1855-1937; Somogy EÌd. D'Art, 2010.

"Illuminated apotheosis of Angkor Wat," special issue of L'illustration. 22 August 1931.

Angkor Wat and Dance

The 1889 Universal Exhibition in Paris saw the first free-standing replica of an Angkor Wat temple in its French colonial section. The dancers from Cambodia, however, performed with other dancers from colonial Southeast Asia at the “Kampong Javanais” (a ‘traditional’ Javanese village). The Angkor Wat replicas for the Colonial Exhibitions in Marseille 1922 and Paris 1931 resembled more and more their 'original' source.[8]

The dancers' magic night performances now took place in front of these grandiose replicas. Eventually invited to perform at the Paris Opera, the troupe was praised again for the 'authenticity, purity and timelessness' of its dances.[9] The 1931 Fair, furthermore, topped all earlier undertakings of exotic representations in scale, variety, and performance. The 'illuminated apotheosis of Angkor [Wat]' reached the 1:1 scale of its Cambodian source and the theatrical effect of its central causeway was enlarged into a cruciform square for cultural performances.[10]

Dance and Architecture

In order to create a sense of cultural authenticity and for the audience to experience the culture as a whole through dance, the Asian dancers performed mostly in architectural setting suggesting their original environment, most importantly, the reduced size recreation of Angkor Wat. This performance and re-enactment of local culture was intended to bring to the world an understanding and appreciation of a given Asian culture as an organic whole.

Emulating Asian Dance

The international impact of the Asian dancers was immediate. Paris, which was at the time the most important center of modern art in including dance, played a critical role and was central to this cultural exchange. Dancers who had congregated from all over the world in Paris rushed to engage with these new dance forms in their own performances. These engagements ranged from efforts at imitation to innovative creations. Examples are Cléo de Mérode’s “Cambodian dances,” Mata Hari’s “Brahmanic dance”, Loïe Fuller’s “Geisha Dance”, and Ruth St. Denis’ “Indian Dance.” Eventually, the new troupes of modern dance such as the Ballets Russes would integrate Asian elements into their own choreography.